Borneo, World War II:

A tale of angst and anguish comes to life as Sarawak languishes between Admiral Lord Mountbatten’s faculty as the British battle through Burma’s hideousness, and General MacArthur’s disinterest whilst the Americans island hop toward Japan.

In a fateful twist of irony however, Sarawak held huge reserves of Japan’s motivation for attacking Pearl Harbour: oil. Beyond the reach and interest of regular forces, the denial of this vital supply of life-blood to Japan fell to an unorthodox British Special Operations Executive officer.

Thwarted by larger campaigns, he recruits an unsuspecting engineer who worked for Sarawak Oilfields Limited – a company the world now knows as Shell – to attack the Japanese working the very oilfields the man had built.

As this engineer-cum-soldier sets out to sever Japan’s fuel jugular, he could have had no premonition of the wrath and venom an unfeeling enemy would vent on a people he had come to know and love.

Aghast, the man is forced into ever more desperate circumstances as what started out as a mission to throttle Japan’s fuel umbilical inexorably mutates into a race for mere survival.

Set in Miri, Sarawak, much of this story is true as one of World War Two’s last secrets comes to light.

ABOUT SARAWAK

Sarawak lies on the north west coast of Borneo and is one of the thirteen states that today make up Malaysia. To declare a total land area of forty-eight thousand square miles, holding a population of slightly over two million is however to tell of only facts and figures, statistics and socio-data.

Sarawak – Land of the Hornbills

It does not tell of a place known as the Land of the Hornbills, a land of untamed jungles that has been touched through time by magic and mystery. Still exotic, in this world of 747’s and A380’s, this is a place where dusty chandeliers of human skulls can still be found hanging from the rafters of seldom-visited longhouses. To this day Sarawak offers a unique experience in this ever more regulated, conformist world.

Though Sarawak’s human history can be traced back forty thousand years, the caves at Niah being the earliest evidence of human settlement in South East Asia, her modern history starts a little more recently.

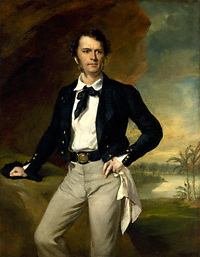

At the beginning of the 19th century Sarawak was loosely controlled by the Brunei Sultanate. In an age of little communication with the outside world, and often less within, a wild, unruly land of headhunters prevailed. In 1841, James Brooke, an English gentleman adventurer sailed to Sarawak to mine antimony. Finding a land troubled by a native uprising he assisted the Sultan of Brunei in quelling the rebellion. Rewarded with a parcel of land, around what is now Kuching, from him emanated a wind of change that washed through this remote, lawless land.

The next century would see three successive generations of Brookes rule these wild terrains through a dynasty known as the White Rajahs. Relentlessly increasing Sarawak’s land mass at Brunei’s expense, the White Rajahs and their administration were much revered and respected by the remote, native peoples they presided over. Determined that the word native should not be regarded as derogatory, as it was in India, Malaya, Sumatra and Java, the paternalistic White Rajahs were accorded a loyalty that survives to this day. Displaced as Japan overran South East Asia in 1941, the White Rajahs never fully returned to this land, relinquishing government to Britain in 1946. To this day however, their unique imprint is still indelibly stamped across Sarawak.

Though Sarawak flourished qualitatively in the century of the White Rajahs tenure, it perhaps did not expand and develop quantitatively at the same pace as the outside world. This slower, more graceful cultivation of place and people left a legacy that till today sets Sarawak aside from the outside world.

Today Sarawak is a polyglot society, a charmed land where people of ethereal grace maintain time to talk to each other and visitors alike. A naturalist’s dream, squirrels that fly are found alongside macacques that dive for crabs. Plant life in the world’s oldest rainforest slips beyond the incredible as pitcher plants trap insects and small rodents in their saxophone like leaves.

Miri: Sarawak’s Oil Town

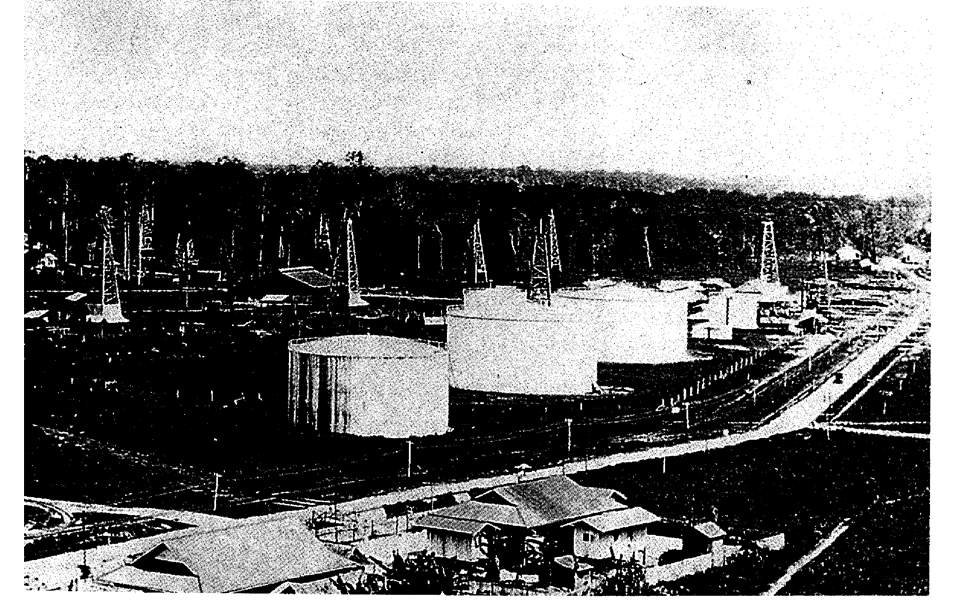

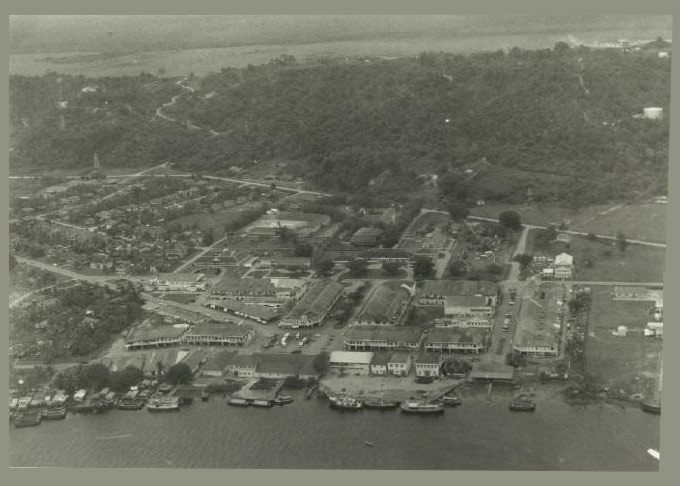

This picture of an infant Miri dates from 1953. It shows a small town with a thriving dockside. If you look closer at the background you will see scattered about a few oil derricks beside Oilfield Road as it twists and turns its way up Canada Hill.

Miri Town, Sarawak, on the northern fringe of Borneo, circa 1953.

You may notice Water Tank #3 on the right, at the place where St Joseph’s Church now stands. What you will not see amongst this orderly grid of roads and streets is the town that it replaced; the town that was sacrificed in 1941 by fleeing expatriates, tortured by the choleric Japanese and obliterated by the Allies as they returned victorious in 1945.

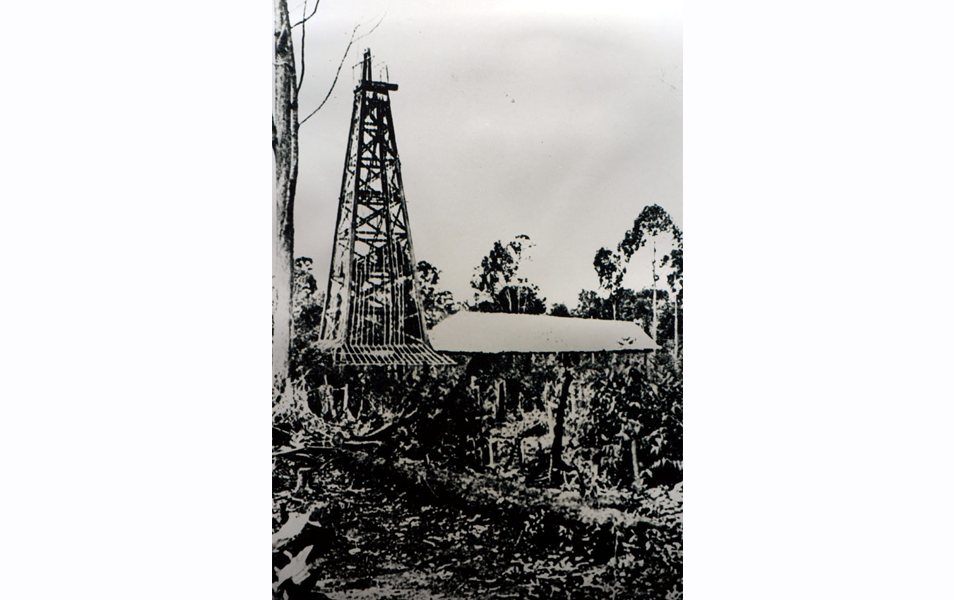

The Beginning of Time.

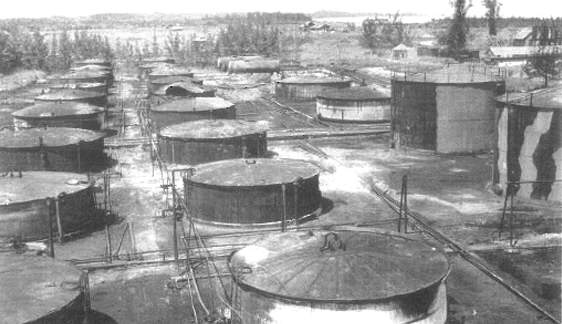

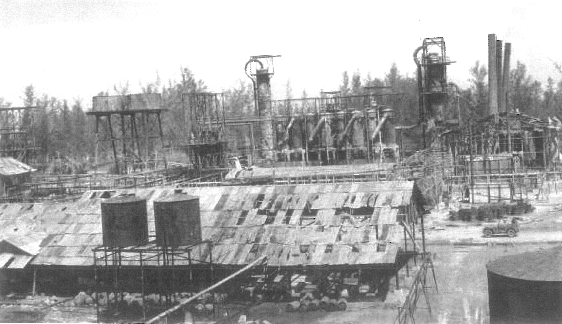

The history of present day Miri essentially begins with the spudding of Well #1 on 10th August, 1910 by Sarawak Oilfields Ltd, the company the world now knows as Shell. The beating back of malarial jungle to entice Miri to bring forth her mineral wealth must have been difficult beyond belief. The physical effort required from the Chinese coolies, who arrived from China to spend their lives in toil and servitude was surely immense.

As the prodigious capacity of the Canada Hill and Pujut oilfields became apparent new technologies had to be developed whilst the ever-encroaching jungle knocked at the back door. These hardy, intelligent and resourceful pioneering men who never knew when to give up, simply battered back any problems to deliver world-class solutions.

By 1935, the neighbouring Seria field, discovered 32 miles up the coast in Brunei, was the British Empire’s most prodigious single field, producing some five million barrels of oil annually.

A World Removed

Life was incredibly difficult for the initial party of eight engineers who prospected Miri for oil. There were no telephones or electricity, only oil lamps at night to counter the blackness of the jungle. Opening up the jungle released hordes of mosquitoes and black cobras. Snakes would secrete themselves in the rafters of the attap houses, to fall onto tables and chairs to the excitement of those at the table.

By the 1930's Miri had been transformed from a sleepy fishing village of twenty dilapidated shacks of the Malay fishermen, a pawn shop and an Arab trader into a bustling small town, imbued with the energy and verve of the industrious Chinese towkays attracted by the burgeoning wealth of the oilfields. Expatriate life in this edge of the Empire town combined hard work with exotica that is lost in today’s modern world.

The Gathering Storm; Why Miri? A Question of Concentric Circles

Place the point of a metaphorical compass in Tokyo and start drawing concentric circles outwards. The first commercial oil reserves you would find in 1941 were those of Miri.

In 1940, Japan imported ninety-five percent of its oil requirements, eighty percent of this from America. In 1941, President Roosevelt cut off all oil exports to the increasingly warlike Japanese. Knowing that she had little time in which to act as her oil stocks dwindled, Japan drew up a plan. By occupying Borneo and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia),whilst the British and Dutch colonialists were embroiled in

a European war, Japan would take possession of the rich oilfields across Sumatra and Borneo.

Japan’s first target would be Miri. But once the oilfields were taken, Japan still had to transport the oil back to the homeland safely. To ensure the safety of this precious lifeblood as it sailed the seas, the Japanese came up with an ingenious plan; they would destroy the American fleet as it lay at anchor in Pearl Harbour.

The Pacific War Erupts

As attack by the Japanese loomed as more of a probability than possibility the British, hanging on for grim death at home, knew that they could not honour the promise of defence that had stood in place with the White Rajah’s Sarawak since 1881. With the geographically isolated Miri essentially indefensible, the British government ordered that a scorched earth policy be adopted.

The scheme, known as Operation Denial, was to bear no consideration whatsoever to re occupation of the facilities following the cessation of hostilities. Destruction was to be total. The only concession to total destruction allowed by the British was that a portion of the equipment from the refinery should be transported for safekeeping to Singapore. Singapore, after all, would never fall.

On the morning of December 15th, 1941 Japanese forces known as the Kawaguchi Detachment landed at Miri. The small local police force surrendered as the few remaining Europeans either fled to the interior or were rounded up for internment. That the Kawaguchi Detachment consisted of some eleven thousand men in ten troop transport ships perhaps illustrates the degree of Japan’s desire to ensure the capture of Miri’s undefended oilfields.

The Japanese Occupation

Marquis Maeda, the first commander of the Japanese Defence Force of Boruneo Kita, as the Japanese renamed Sarawak, was a leader of great style and panache. Charged with bringing back on stream the destroyed oilfields, the task was made significantly easier as Miri’s oilfield equipment sent to Singapore for safekeeping was returned intact. With repairs to the oilfields well underway, and wanting to further his effect across the region Maeda installed himself in the White Rajah’s palace; the Astana at Kuching. Though at the opposite end of Sarawak from the all-important oilfields, Maeda determined himself to fly, something he enjoyed immensely as he would often order pilots to perform aerobatics for him, as he set out to woo the sultans he needed support from. To make a clean, symbolic break from the White Rajah’s administration, Maeda ordered the cutting down of the vines that traditionally clung to the walls of the Astana. To the uncomplicated, superstitious people of Sarawak, who Maeda regarded as simple pagans, the removal of the vines brought with it a death curse. Within months of the vines being cut down, on the 5th September, 1942 the plane carrying Marquis Maeda crashed into the sea between Miri and Kuching, killing both Maeda and his pilot, in an accident history attributes to pilot error.

Of Massacres and Murders

The following paragraphs are extracts from a British Army Report by Lieutenant Colonel John Eyre concerning the massacre of Europeans by Japanese forces at Long Lawan, Borneo, February, 1942;

- I am setting out a timetable of the events immediately preceding the massacre, in Appendix III to this Part. In brief, the men were killed first, the women several weeks later. In the meantime there is a possibility that some of the women were used for the sexual gratification of their captors.

- Again, the matter in which the children met their deaths is not clear. Three methods are suggested as follows;

- they were set at large and shot down indiscriminately;

- they were persuaded to climb into a tall tree beside the Padang, and used for the purposes of target practice;

- they were bayoneted to death.

- A similar difficulty surrounds the manner of the death of the women. Here again there are three alternatives, in respect of each of which there is some colour of evidence, as follows;

- they were lined up and bayoneted to death;

- they were shot;

- they were hung in sacks and killed by bayonet.

Of these three alternatives a certain amount of medical evidence suggests that the last is the more probable.

War today has become a media highlight, dreadful images trammelled onto flat-screen TVs to be ogled at from the comfort and safety of armchairs and exercise bikes. It has not always been so.

Imagine the fear enveloping expatriates in 1940’s Sarawak with Europe consumed by war, America clinging to the sidelines as Japan rattled its imperial sabre in search of the commodities it craved; commodities that Miri held in profusion.

The expatriate families of Miri in 1941 did not need to imagine this. Caught by Japanese forces at Long Lawan as they fled, wives watched numbly for two horrific weeks as husbands were murdered first, their children then shot callously before they each soiled themselves as, one by one, they were hung in sacks to be used for bayonet practice.

Once Japan had crushed all opposition, she set about rejuvenating Miri’s destroyed oilfields in a manner that was sadly typical of that time.

The main source of labour used by the Japanese for the repair of the oilfields was that of slave labour. Known as Ramusha, they were Javanese. Literally available by the boatload, they were denied food from arrival. Life expectancy for these unfortunate souls was around three months. To galvanise others to work harder, the Japanese guards would often single out a weaker soul and beat him to death as an example to the other Ramusha.

The last act of the callous Japanese in Miri was the mass murder of twenty-eight innocent men, tortured pointlessly as tales of Allied parachutists in the interior circulated Miri. Unable to reply to the ridiculous demands battered into them, the men were made to dig a large hole just out of town at Lopeng. The men were then machine gunned just months before the Japanese capitulation.

The Allies Return

Determined to strike at the valuable oilfields, and frightened for the fate of the prisoners of the Japanese, the Allies parachuted into Bario, in the highlands of the interior, from where they would fight a war from within.

Led by an Englishman, the recalcitrant Major Tom Harrisson, Australian commandoes parachuted into Sarawak’s interior in March 1945. In total, four teams operated in Sarawak, known as Semut, whilst two further teams, known as Agas, operated in British North Borneo – now known as Sabah.

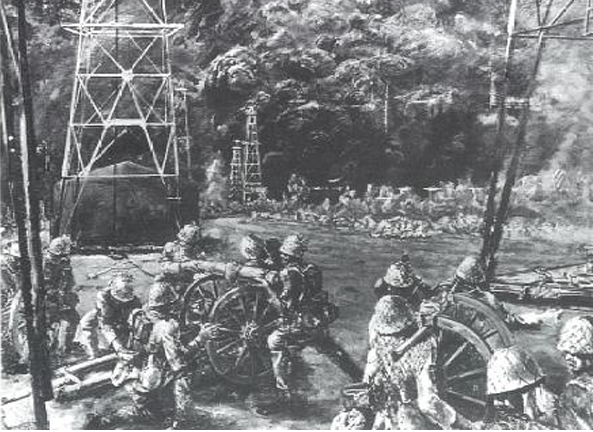

The mission to retake Borneo, Operation Oboe, involved Australian forces in a series of landings along the Borneo coast. Working east to west heavy casualties were initially suffered at Balikpapan and Tarakan Island. Though many lives were lost in retaking Labuan Island, off Brunei, the Japanese had essentially lost the will to fight as the Australian 9th Army landed at Miri. The Japanese, after firing the oilfields, fled into the jungles where the waiting Semut teams picked them off mercilessly.

Of all of the covert operations carried out by Australia’s Services Reconnaisance Department, none came close to the success achieved by the Semut teams. Semut I, commanded by Harrisson, led native forces in taking the heads of over a thousand Japanese soldiers throughout the inhospitable jungles of Borneo as the Japanese fled the main Australian landings at the coast.

And In The End

By 1935 Miri was a fine, industrious pearl of the Orient. As is so often the case however, the brunt of warfare is borne by those not equipped to fight back. By the time the Australian forces had returned, the small, thriving town that Miri had been was gone, obliterated by an Allied bombing campaign. That the Japanese surrendered just months later was of no real concern to the people of Miri. Once scores had been settled with Japanese collaborators, the townsfolk of Miri set about to rebuild their destroyed town.

A visitor to Miri today would barely see the scars of the blighted years of Japanese occupation. For such a small, out of the way town, its importance to the Japanese warmongers provided a real life drama that does down Hollywood’s single digit IQ action movies of today. Into these incredible times and people is woven the thread of A Leopard Sings in Sarawak.

Take a trip into A Leopard Sings in Sarawak now – hit the Samples tab for selected scenes that will immerse you in the flavour of exotica, passion and horror that make up A Leopard Sings in Sarawak.

Toby Carter

Gordon Senior (Toby) Carter shares more in common with the fictional lead character of A Leopard Sings In Sarawak, Geoffrey Portas, than any other person that lived through that monumental era. It is shuddering to think how the fictional character Geoffrey Portas survived the angst of having to leave a recently discovered paradise as the Japanese Occupation ensued, only to have to parachute back in to fight for everything he believed in and held dear. Toby Carter made these harrowing decisions for real and lived to tell the tale.

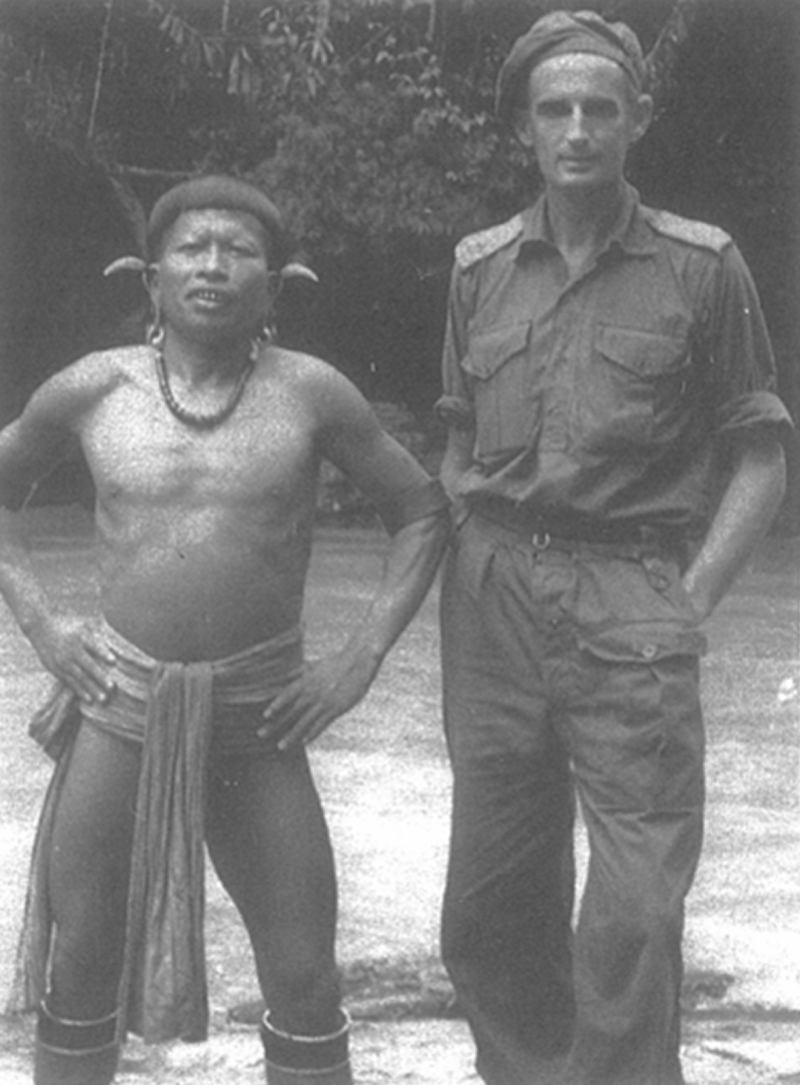

Toby Carter with a Kelabit Chief at Long Lelang

A New Zealander, Toby Carter joined Sarawak Oilfields Limited in 1935. Working as a surveyor he was responsible for exploration of the Baram and Tinjar river basins - the epicentre of A Leopard Sings In Sarawak. Here he lived for long periods with the native tribes, sharing their longhouses and learning their languages as he mapped these previously uncharted regions.

Teaming up with Tom Harrisson, seconded from Britain, Toby was initially a supporter of insertion by submarine rather than by parachute. He did attend parachute training but was withdrawn during the course due to being ‘not best matched’ to the rigours involved. With this aversion in mind, Toby still eventually concurred with Harrisson’s desire to use parachutes. The final decision was prompted when another ex-Sarawak Oilfield’s surveyor, Dr W. F. Schneeberger, highlighted several locations on Borneo’s central plateau ideally suited to parachute operations.

Leading the Semut II team in the Baram and Tutoh river basins from the old fort at Long Akah, Major Carter successfully inspired a campaign of insurgency against Japanese troops in the area, being awarded a Distinguished Service Order.

Carter, more than any other Semut member, at all times kept his eye on the end game – what would happen when the Japanese capitulated in Sarawak? Following the war Toby Carter rejoined Sarawak Oilfields and became a senior member of staff as the oilfields of Miri and Brunei were rebuilt following their destruction by the Japanese.

Tom Harrisson: The Most Offending Soul Alive

"Explorer, museum curator, guerrilla fighter, pioneer sociologist, documentary filmmaker, anthropologist - Tom Harrisson was all these things. He was also arrogant, choleric, swashbuckling, often drunk and nearly always deliberately outrageous. In spite of these contradictions, he became a key figure in every enterprise he undertook. "

-Sir David Attenborough

Tom Harrison at Bario; March, 1945

An English eccentric and adventurer, Tom Harnett Harrisson (1911-1976) sought knowledge and renown in a dizzying number of fields; whilst breaking most of the rules of civilized society.

A charismatic figure, who offended as many people as he impressed, he chose to live life in the twilight of colonialism on the fringes of the British Empire.

Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, to Brigadier General Geoffrey Harnett Harrisson and Marie Ellen Cole, Tom Harrisson’s first contact with Borneo came when, at the age of twenty-one, as a keen ornithologist, he led an Oxford University Expedition to Sarawak in 1932 after quitting his studies at Cambridge University after a year of drunken escapades and generally thumbing his nose at society.

Immediately forming an affinity with the longhouse dwelling peoples he found in Sarawak’s river basins, Harrisson for evermore fitted in better with primitive peoples and working class people than he did his own class.

Another expedition, to the New Hebrides resulted in Harrisson penning the best selling book ‘Savage Civilisation’ in 1937.

Back in England Harrisson’s life suffered for the want of the university degree, pushing him to work in Bolton’s cotton mills and as a lorry driver before pioneering Mass-Observation with Charles Madge. This would be the forerunner of market research and various sociology tools in use today.

In 1944 Harrisson was approached by Britain’s Special Operations Executive looking to help their Australian counterparts by providing knowledge of Borneo’s then little known interior. In March 1945 Major Tom Harrisson parachuted into Bario, a remote, relatively unknown plateau in the highlands of Sarawak, with seven Australian commandoes.

Operation Semut accounted for some fifteen hundred Japanese killed or captured, losing only a handful of the blowpipe toting Sarawakians that had been recruited. This mission, by far the most successful of any of Australia’s covert WWII operations, is drawn on largely in A Leopard Sings In Sarawak as the struggle of the central character nears its conclusion, and is described excellently in Tom Harrisson’s own excellent 1959 book: World Within.

After the war Harrisson settled in Borneo, where, as curator of the Sarawak Museum, he transformed it into a model and inspiration for the region; he led efforts to save the orangutan, the green sea turtle, and other endangered species; he discovered the oldest modern human skull known at the time; he published widely in the scientific and popular press, and appeared frequently on the BBC and British television.

A man with tremendous breadth of interest and vision, Harrisson continually sought ways to connect knowledge across disciplines, alienating in the process more narrowly focused academics who resented his encroachments - and his lack of a university degree. Yet a number of his ideas, particularly in anthropology and archaeology, seem modern today.

Tom Harrisson died in a road accident in Thailand in 1976.

A Leopard Sings in Sarawak

652 Pages

Language: English

ISBN-978-967-13640-2-4

Size: 14.8cm X 21cm