Synopsis

The briefest mention of South East Asian communism unerringly swirls the mind to Vietnam, a place where screaming jet-fighters, Napalm and Agent Orange were defeated by steely resolve. A war bogged down in impossible rainforests, tenacious villagers in straw hats inflicted a humbling defeat on the greatest military power the world had ever known.

Before Vietnam erupted, however, there had already been a war between the West and Asian communism.

The place was Malaya, where between 1948 and 1960 a long and bitter war was fought in South East Asia’s jungles for the wealthiest of colonies. How then, did Britain and her Commonwealth allies silently defeat Malaya’s communists?

It was to this little known battlefield that Major John McCawley of the British Special Operations Executive shifted his focus before Hiroshima’s atomic fallout had settled.

Leaving Brisbane behind, from where he had thought and planned for his parties of stay -behind commandoes in Japanese occupied Malaya, he would now battle and scheme to outwit the Communist Party of Malaya.

Carrying the fight to the Communist Tigers as Malaya tore herself apart, John McCawley could have had no idea of the dreadful consequences that would befall both friend and foe, those he loved and those he loathed.

Pre-war Malaya – A Land of Milk and Honey

“A first-rate country for second-rate people” said Somerset Maugham of pre-war Malaya. Whether he was referring to love-struck colonial bachelors of no great charm or fortune surrounded by gorgeous, willing girls, or of imperious Mems battling boredom in luxurious homes, pampered by pliable servants they could ill-afford at Home, it is difficult to say.

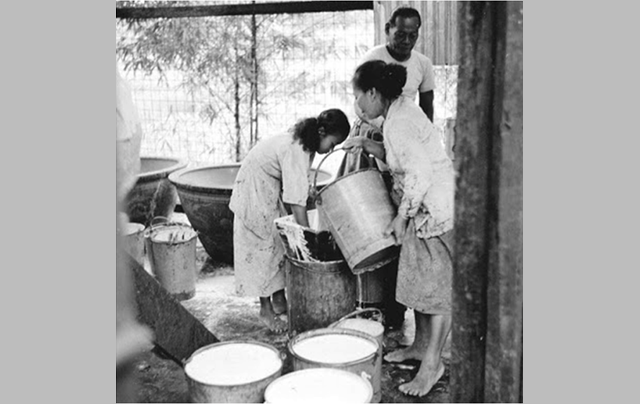

Whilst plantation life may have been luxurious though lonely for European tuans, it was a hard, austere existence for the imported Tamil and Chinese rubber tappers. Trapped by poverty, their day’s work started at sunrise. Expected to each tap five hundred trees in a single day, the back-breaking work caused premature old age as a spectrum of maladies afflicted the over-worked souls as they toiled the day away in tropical heat, either tapping rubber trees or smoking rubber sheets. Returning each evening to tiny sleeping-cells, they struggled to survive in the overheating accommodation that the little-caring, multi-national plantation companies provided along with subsistence wages.

For a glimpse into their everyday existence hit the link; http://vimeo.com/19018353

Rubber Planters and Tin Miners

Malaya’s first sources of modern-day wealth were the rubber plantations and tin mines that sprouted in profusion in this most blessed of lands.

In what must rank alongside any industrial undertaking the world has ever seen, the rolling back of Malaya’s jungles in search of land for rubber plantations was indeed a miracle of brawn and brains. The size of the task can only be comprehended when one recognises that these two industries brought Tamil tappers and Chinese coolies to Malaya in such huge numbers to service this work that modern Malaysia’s multi-cultural society was unknowingly welded in place.

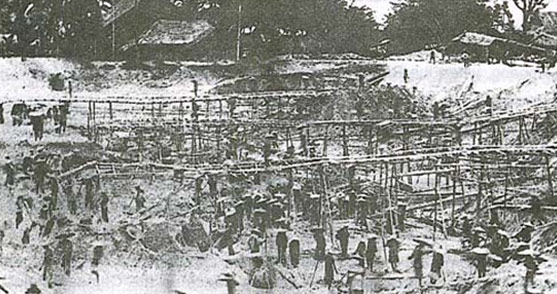

Despite romantically held notions of Gone With The Wind-type plantations, the brutal reality was that millions-upon-millions of acres of jungle and swamp were cleared, drained, terraced and planted with rubber trees one hundred and twenty to the acre in dire, slavish conditions.

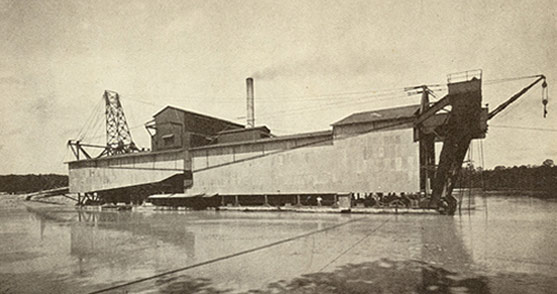

Tin mines, immense and tiny, dotted the peninsula as the world’s desire for canned food drove China’s Kongsi houses and London’s Square Mile to invest men and machinery in Malaya’s scarring, blighting business of tin. The technologies employed by the British mining agencies and the Chinese Kongsi houses were as different as the ventures themselves.

Utilising Mainland China’s bottomless pit of cheap, ant-like labour, China’s insatiable conglomerates employed nothing more complicated than water cannon and bamboo scaffolds to exploit surface deposits. The British, bringing huge financial strength to bear, opted for massive, complicated dredges that produced phenomenal quantities of tin. Both methods were ecological disaster zones that are often now home to delightful inner-city lakes and parks in Malaysia.

New Villages

Across today’s Malaysia lay many identically named villages within a stones throw of each other, identically named except that one will be suffixed “Bahru” – Malay for New. Separated by barely a mile, Ulu Yam and Ulu Yam Bahru in Northern Selangor are typical of this trait. But why? What drove this national quirk?

As the British returned to post-war Malaya they discovered astounding numbers of Chinese squatters. Victimised and tormented by an uncaring, authoritarian Japanese master, almost six hundred thousand Chinese fled Malaya’s towns to eke out a subsistence survival rearing pigs and growing vegetables on the fringes of ever-present jungle.

An industrious impediment of unfathomable scale producing Malaya’s food, they were allowed to stay on land they did not own. Temporary residence permits were issued by the British, allowing the food production Malaya depended upon on land predominantly owned by the Malay sultanates.

The British Army would resettle whole encampments of squatters, their possessions and pigs included, at a single time.

It was this vast, untethered populous that the communists considered would be their secret weapon, rising up as the hard line communists lit the blue touchpaper of insurrection. Stirred by the Min Yuen – the communist’s People’s Movement – or threatened by communist terrorists from the jungle, it was these squatters who were to provide the intelligence, food, weapons and money that the uprising required.

As Malaya was being bludgeoned at will by the communists through 1949 the British recognised that drastic action was required if Malaya was to be saved. Realising that military might alone was inadequate to defeat a guerrilla war being fought from Malaya’s concealing jungles, the British hatched an audacious plan that until today make the campaigns in Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria look small and amateur. The British announced to a disbelieving world that six hundred thousand Chinese squatters were to be relocated lock, stock and barrel to new villages to remove them from the clutches of communists who could vanish at will. Working hand-in-hand with the Malay sultans and newly formed Malayan Chinese Association, land was alienated, townships built and squatters relocated in a tidal wave rolling south to north up the Malay Peninsula in a scheme known as The Briggs Plan after the then military supremo Lieutenant General Sir Harold Briggs.

As the squatters were moved into the new settlements, often forcibly, support for the communists evaporated. Food controls put in place denied sustenance to those fighting from jungle hideouts. Removing people from the opportunity for coercion gladly wielded by the communists, intelligence trails withered and died, leaving the communists stranded.

Whole communities lived encaged, their lives controlled and regulated.

Not all went well initially. Houses often remained ramshackle even when families grew wealthy, scared of enforced subscriptions for the communists and perceived tax payments to a government they did not trust. Rudimentary initially, people eventually melded into communities, determined to provide a future for themselves and their children as they gradually built new lives.

The scale involved proves that the plan was brilliant. Of the four hundred and eighty new villages established by 1954, four hundred and fifty remain today.

A typical high street of a New Village. Rudimentary initially, over three generations they transformed into caring, successful communities

The Communist Party of Malaya

Who were Malaya’s communists? How did they compare to Vietnam’s infinitely more known and recognised communists, and who defeated them?

Centred in Singapore, the predominantly ethnic-Chinese Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) was an outlawed organisation prior to the outbreak of the Pacific War. Desperate for a support base in an envisaged lengthy guerrilla war, the British hastily struck a deal with the communists as the Japanese Imperial Army pelted down the Malay Peninsula.

Trained and supplied by the British, the communists morphed into the Malayan Peoples Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). Working hand-in-hand with Britain’s covert Force 136, the numbers of MPAJA fighters ballooned from an initial two hundred at the outbreak of the war to around five thousand by the time the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki drained Japanese will.

Provided political recognition by the British in return for their wartime support, the CPM remained essentially ethnic-Chinese post-war. Adopting a surprisingly low-key, subdued policy of union infiltration and promotion of labour strikes, by the time the CPM realised it had been sidestepped by the British as they dealt with the Malays it was June 1948 before the CPM brought war back to Malaya.

Given the understated nature of the Malayan Emergency in comparison to the world-renowned Vietnam War, it is poignant to make several fundamental comparisons of the communist forces at the outset of each of these campaigns. In Malaya there were some five thousand active communist guerrillas who returned to their jungle camps in 1948, supported by a nominal fifty thousand covert Min Yuen (Peoples’ Army) who remained at large in the population, arranging food and money, gleaning intelligence as they worked as waiters and washerwomen or the like. In 1959 the corresponding Vietcong numbers were also five thousand guerrillas, supported by as many as one hundred thousand supporters in a country approximately twice the size of Malaya. In both cases these numbers represent less than one percent of the respective populations.

It would, however, be unfair to draw such direct comparisons whilst avoiding the differences when considering the reasons for the different end results of the two wars against Asian communism. People, cultures, religion, climate, terrain, wealth, development, authority and governance all showed marked divisions between 1948 Malaya and 1959 Vietnam. The prime, telling difference between the two campaigns however were policies that drove Malaya’s communists away from their support networks, whilst North Vietnam continuously maintained a line of aid to the South’s communists. Whilst many of the differences highlighted here undoubtedly favour communism’s enemies in Malaya, the lack of a plan or system to limit and suffocate North Vietnam’s line of troops and equipment to the South ultimately led to communism’s victory in Vietnam.

Once Malaya’s communists had been isolated from the Min Yuen, Britain’s advantage in Malaya, where they had an effective authority network in place, allowed them to implement a police controlled, military style campaign that drove the guerrillas into ever-deeper jungle.

The mastermind behind the plan was Lieutenant General Sir Harold Briggs. Hardly a household name this quiet, hard-working man devised a plan of belief-defying scale to first isolate then eradicate Malaya’s communists.

Working himself towards an early grave, Briggs left Malaya before the job was complete. The men who followed Briggs in shepherding Malaya to peace and independence introduced no significant changes to the masterful Briggs Plan. As well as defeating communism, the campaign Briggs inspired took the remnants of Britain’s wartime Special Operations Executive and forged it into the world’s first and best elite military force; the Special Air Service.

Not since the Malayan Emergency has a military campaign against communists or terrorists been successful, yet it remains hidden beneath a cloak of silence.

Chin Peng; Successor to Lai Teck

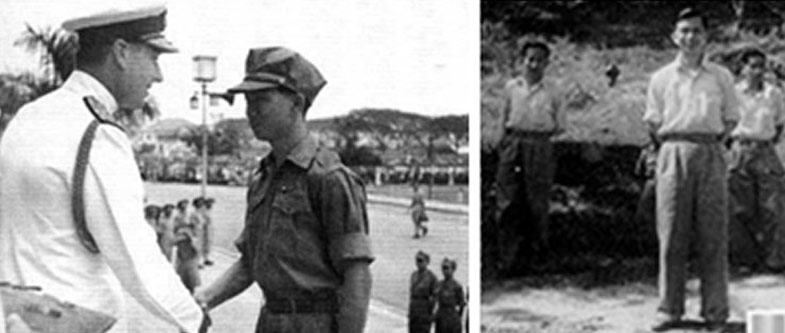

Chin Peng, born October 21 1924, died September 16 2013.

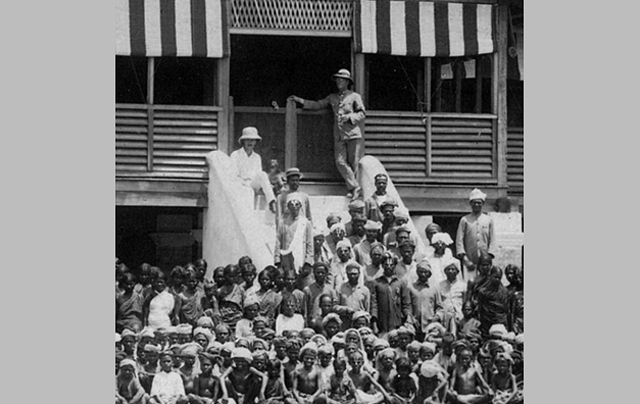

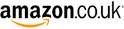

Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army fighter Chin Peng receiving his campaign medal from Admiral Lord Mountbatten at Singapore in 1945, and as leader of the Communist Party of Malaya leading the communist contingent at the Baling Peace Talks in 1956

The following is Chin Peng’s obituary from the British Telegraph newspaper:

Chin Peng, who has died aged about 88, was decorated for his bravery fighting alongside British forces in the Second World War then afterwards took up arms against them in the Malayan Emergency.

His fight continued even after Malaya achieved independence in 1957, and it was only in 1989 that he signed a peace treaty with the government of what was by then Malaysia. Even so, he continued to be prevented from returning from exile to the land of his birth, where he remained a divisive figure.

Ong Boon Hua is thought to have been born on October 21 1924 in Sitiawan, a small town in the state of Perak in the Malayan peninsular that bordered southern Thailand. He was the son of a bicycle dealer who had emigrated from Fujian province in south-east China: it would be Malaya’s ethnic-Chinese population which took up arms most willingly against the Japanese during the war; feeling themselves to be a disenfranchised minority, however, it was also they who formed the spine of the postwar communist insurgency against Britain.

Chin Peng, as he would be known on the battlefield, was a studious youth, learning English at the Methodist School in Perak. At 15 he joined the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) and began work in the design department of Perak’s Humanity News.

He was close to the CPM’s leader Lai Teck, and his political rise was swift. But war would interrupt his ascent. After the Japanese invasion in December 1941 the CPM formed the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). From February 1942 to the end of the war the MPAJA took on Japanese forces, often with Britain providing weapons and training.

Chin Peng was an MPAJA liaison with British officers (many from Force 136, a south-east Asian variant of the Special Operations Executive). In an interview in 2009, Chin Peng recalled cycling from his home to the coastal town of Lumut to meet British operatives who had arrived by submarine: “I used the trunk roads and then the estate roads to avoid being spotted. I cycled everywhere.”

For his contribution to the Allied war effort, Chin Peng was decorated with the Burma Star and appointed OBE. The latter would soon be rescinded as Peng segued from wartime hero to colonial villain.

After the Japanese surrender in August 1945 the MPAJA took control before British authority was restored that autumn. In the brief interregnum, reprisals were severe. The ethnic-Chinese MPAJA accused many ethnic-Malays of collaborating with the Japanese. Ethnic-Malays, meanwhile, would accuse the MPAJA of indiscriminate violence.

With the return of British rule, the CPM campaigned for independence. When it became clear that this would not be forthcoming, the party went underground. Leader Lai Teck was accused of being a spy and fled leaving Chin Peng, aged 24, to take control.

He immediately abandoned Lai Teck’s moderate stance, advocating instead violent struggle on top of strike action as the best means to establish a communist state in Malaya and Singapore. On June 16 1948 this new aggression was announced when CPM fighters attacked two rubber plantations in northern Malaya and murdered three British planters. Though he always denied personally ordering the killings, Chin remained unrepentant about them. “We considered the European planters as a symbol of colonial rule,” he said. “They were hated by the workers.

“I make no apologies for seeking to replace such an odious system with a form of Marxist socialism. Colonial exploitation, irrespective of who were the masters, Japanese or British, was morally wrong. If you saw how the returning British functioned the way I did, you would know why I chose arms.”

Days later British authorities declared an Emergency, beginning a 12-year conflict that amounted to a war in all but name. The communists could count on up to 10,000 insurgents; Britain dispatched tens of thousands of Commonwealth troops. Chin Peng’s tactics were clear: rely on the support of ethnic-Chinese smallholders on the fringes of the jungle, then retreat into that jungle when British troops moved in.

To counter this, in 1950 Sir Harold Briggs organised the resettlement of half a million largely ethnic-Chinese in hundreds of “New Villages” away from the jungle redoubts of the CPM. Cut off from the sources of food and support, Chin’s forces became besieged.

This did not prevent the assassination of the British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney, in October 1951, but the tide of conflict was turning. Having isolated Chin’s forces, British troops began aggressive patrols of the jungle. Slowly but surely Chin’s men were hunted down. CPM attacks fell dramatically.

By 1955 the Malayan government offered communist insurgents an amnesty before, at the end of the year, the two sides met for talks. Chin Peng was not in emollient mood. He demanded recognition of the CPM and acceptance of its role in political life. “If you demand our surrender,” he noted, “we would prefer to fight to the last man.”

The talks collapsed and the amnesty was withdrawn. Despite half-hearted efforts to re-launch negotiations, it quickly became apparent that Britain was preparing to grant Malaya independence, stripping the insurgency of its raison d’être. Yet Chin considered the government of the newly-independent country colonial stooges, and some of his fighters continued to launch attacks into 1958. Most fled across the border into southern Thailand, however, and by 1960 Malaya declared the Emergency over. Chin Peng left Thailand for Beijing.

There he spent much of the next decades. Assured that south-east Asia was ripe for revolution, the CPM continued to maintain a base in southern Thailand. But revolution never materialised, and in the course of the 1970s the CPM was riven by bloody infighting. Finally, on December 2 1989, a peace agreement was signed by the Malaysian and Thai governments and the CPM.

Chin, unrepentant for his role in a 40-year conflict which cost many thousands of lives, appealed – unsuccessfully – to be allowed to returned to Malaysia.

He is reported to have married Lee Kwan Wa, with whom he had two sons.

Lai Teck – Secretary General; Communist Party of Malaya

Vietnamese, Lai Teck was born Hoang A Nhac in 1901 in the Nghe Tinh province of Annam to Chinese, or Chinese Annamese parents.

From an early age Hoang A Nhac embroiled himself in the underworld of Asia’s port cities, drawn, some say, by the romance and excitement offered in the illicit, underhand world of politics and corruption. This exciting, colourful life had begun as he was attracted to communism in Saigon early in the 1920’s, changing his name to Truong Phuoc Dat. Joining the French navy, he jumped ship as he faced arrest for spreading communist ideals throughout the lower ranks. Surfacing next in Hong Kong, he spent several years permeating the revolutionary circles of wealthy, capitalist, polyglot cities such as Shanghai and Macau, becoming further immersed in communist principles as he recognised his route to success.

Arrested at Mukden, en-route to Moscow Truong Phuoc Dat was imprisoned, only to be released in a general amnesty as the Japanese invaded Manchuria. Appearing next in Shanghai, in the shabby, seedier side of the French Concession quarter of the city he was again arrested, and deported to Vietnam. Manoeuvred into working for the Surete in Saigon, he began the shadowy life of a double agent. Exposed in 1934 whilst working undercover in Annam, and so of no further value to the French, he was sent to the British in Hong Kong with a letter to that simply read ‘This man is useful’.

The British, wanting an informer in the emergent, illegal Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), provided Truong with seized communist documents and packed him off to Singapore to work for them as a double agent under the assumed name Lai Teck. By the outbreak of war in Europe the flamboyant communist, who had a taste for the finer things in life, had been elected Secretary General of the CPM and was known fondly to the rank and file as Ah Le – Our Lenin.

In December 1941, as the Japanese were marauding down Malaya and the British were putting in place the final touches to their stay behind parties, Lai Teck covertly met Innes Tremlett, head of the Malaya section of the British Special Operations Executive at a communist safe house; a room above a charcoal dispensary in the Geylang area of Singapore. It was at this secret rendezvous that the British had agreed and arranged the arming of the CPM who would help British-led guerrillas fight the Japanese in the jungles of Malaya in return for post-war legal recognition.

As Singapore had fallen Lai Teck had not followed his minions into the jungle as the CPM morphed into the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). Instead he had remained in Singapore, his knack for suburban subterfuge apparently keeping him alive and well in the underbelly of the cosmopolitan city. Arrested in the Sook Ching, the exercise to eliminate Chinese opposition in which over fifty thousand Chinese men were executed in Singapore, Lai Teck’s reputation as a master of the dark world of the secret agent was further burnished within the CPM as he apparently sowed the seeds of confusion throughout the Kempetai to win back his freedom.

Opposed to what was the popular belief of the communist rank and file, Lai Teck had not confused and bamboozled the Kempetai. Instead he had very quickly struck a deal with the Japanese arresting officer, Major Satorou Onishi. Revealing quickly during interrogation that he was the Secretary General of the CPM it was obvious to both men that he was in a position of great advantage to the Japanese, effectively becoming a triple agent.

The greatest betrayal, though nonetheless just one of an ongoing series during the war, was that which took place at Batu Caves. In August, 1942 Lai Teck alerted Onishi to a high level meeting of the MPAJA that was to be held at Batu Caves, a limestone monolith honeycombed with caves that had become a Hindu temple just outside Kuala Lumpur. On the 1st September the Japanese swooped, killing twenty-nine delegates and bodyguards, capturing another fifteen. It had been a massive blow to the MPAJA. Lai Teck had not been there, claiming his Morris 8 suffered mechanical problems on the long drive up country from Singapore.

Vital to any secret agent, Lai Teck harboured a dispassionate detachment which had seen him survive a career in which he had had the ability to disengage from one faltering cause to take up arms with another embryonic, evolving, subversive movement. It was this quality with which he courted the returning British in 1945. Allowing himself to be manipulated, he stymied communist aggression as the British re-established themselves in post-war Malaya.

Lai Teck vanished from Kuala Lumpur in early 1947, virtually bankrupting the CPM in the process. He was never seen again.

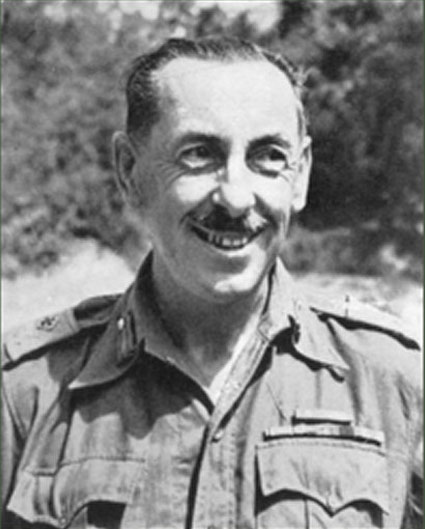

Sir Harold Rawdon Briggs

If modern-day Malaysia owes a debt of gratitude to one man more than any other, it is Lieutenant General Sir Harold Rawdon Briggs.

Though no roads or parks across Malaysia commemorate this quiet, unassuming man, it is his inspired plan that delivered Malaya away from years of being mired by communist inspired poverty and oppression.

A career soldier, he fought in both world wars and a splurge of lesser actions between.

Field Marshal Viscount William Slim said of him "I know of few commanders who made as many immediate and critical decisions on every step of the ladder of promotion, and I know of none who made so few mistakes."

Coming out of retirement in Cyprus, his decisions in Malaya resulted in The Briggs Plan, the action that resulted in the defeat of communism in Malaya. The personal cost to Briggs was that of his health. Within a year of returning to Cyprus from Malaya he was dead.

General Gerald Walter Robert Templer

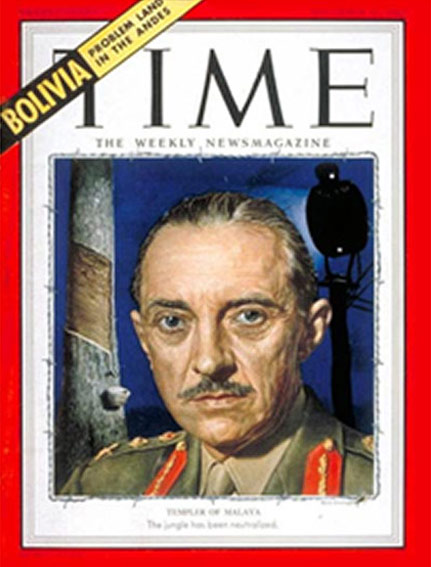

Ask the majority of today’s prosperous Malaysians why Templer’s Park at Rawang is so named and you will most likely be confronted by silence. The above cover of Time Magazine featuring Templer offers clues when you consider the huge searchlight in the background illuminating a rubber tree in a plantation.

Appointed British High Commissioner of Malaya by Winston Churchill, it was Templer who took the Malayan Emergency by the scruff of the neck and dragged the country towards the independence it so craved.

Arriving in January, 1952 Templer remained in Malaya for only two years. In that time he achieved Malayan citizenship for the multitude of Indian and Chinese immigrants as he strove for equality for all Malayans and set in place a democracy that survives to this day.

Typical of his gruff approach to life’s problems as he prepared to leave Malaya was his response to the article in the above Time Magazine that suggested that the communist terrorist situation in the jungle had been stabilised.

“I’ll shoot the bastard who says that this Emergency is over!” growled Templer.

The Tiger Outside The Cage

572 Pages

Language: English

ISBN-978-967-13640-3-1

Size: 14.8cm X 21cm